Am I a feminist? The semantics were never fully convincing to Mahamuda Rahman, a writer and communication officer at Cordaid. That’s why she embarked on a journey to explore this historically charged term. In this blog, she would like to take you on board.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica says feminism is ‘the belief in social, economic, and political equality of the sexes.’ In other words, the feminist movement strives for gender equality and justice. This includes everyone, everywhere.

However, the word itself does not try hard to hide its obvious roots. Feminism has always been about standing up for women treated inferior to men in every sphere of life throughout human history.

How has the straightforward meaning of feminism morphed into a definition that includes equality for all sexes?

Let’s be fran…cesca?

Feminism was originally a movement for women’s rights—or, to be a bit more frank and precise, for middle-class, white women’s rights. As far as we know, the movement was born in Europe and the United States at a time when most of the world was still trying to free itself from the burden of colonisation and its irreparable damage.

A woman of colour might not only encounter sexist discrimination but is also likely to experience racism, as some kind of a cruel package deal.

Over time, the movement started expanding. Women of colour joined and taught the world about the additional layers of oppression and exclusion they face.

Let’s face it: when looking for job opportunities or trying to access basic needs, like health care, a woman of colour might not only encounter sexist discrimination but is also likely to experience racism as some kind of a cruel package deal.

A poor woman of colour will have another layer of exclusion to deal with. And just imagine if she had a chronic disease or a disability on top of all that. On top of just being…her.

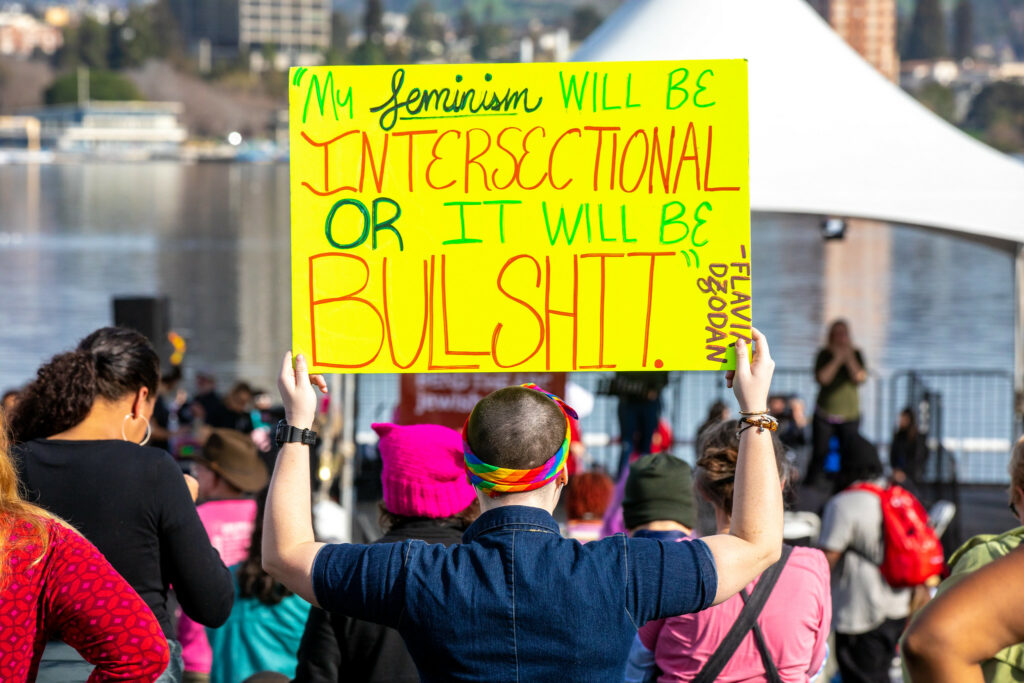

Intersectionality

Now, we are talking about intersectionality. The African American scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw defined intersectionality ‘as a metaphor for understanding how multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves and create obstacles that often are not understood among conventional ways of thinking’.

The voices from different backgrounds, religions, ethnicities, gender identities and sexual orientations taught us that women’s rights are not stand-alone issues and not only about fighting patriarchy. These issues are interconnected with other injustices like colonisation, race, and class discrimination.

So, when feminism transcended middle-class white women’s rights and became all women’s rights, it started to identify itself with other systems of oppression that chain the majority of the world population.

Feminism has been an organic, living, breathing movement that has collected many allies along the way. These are people who are also being treated as second-class citizens, deprived or excluded in one way or another.

In the end, it’s quite simple

If you see things from an intersectional perspective, a poor man of colour faces more hurdles than a white, highly educated, wealthy woman. So, in the end, it’s quite simple: the entire world suffers from inequality and the excesses of capitalism, including many men. Only a handful of people at the top reap all the profits and live like gods.

Should we see feminism as the exact opposite of patriarchy? Perhaps not quite.

Capitalism teaches people to become more self-centred, focusing on their gains and greed. So-called ‘growth’, mindless industrialisation, consumerism, and neoliberalism endanger all living things. In this context, feminism must aspire to oppose all destructive forces of capitalism.

Feminism demands justice and equality for all. ‘Nobody’s free until everybody’s free’, said US civil rights (and feminist) activist Fannie Lou Hamer in 1971.

Feminism versus patriarchy

Should we see feminism as the exact opposite of patriarchy? Perhaps not quite. In a patriarchal setting, the father and the man have all the power. The last thing we need is women copying the type of power-hungry, controlling conduct that has caused so much harm in the world.

In debates about equality, some people like to emphasise the hierarchy in the animal world, as if it were some kind of law of nature that also applies to humankind. Ironically enough, often, these are the same people who claim that we are very different from animals and that our species somehow has the right to rule over all the rest.

What kind of animal produces so much food and stuff, too much to consume, while destroying their habitat? While others remain hungry, homeless and cold. Rest assured: no other animal on this planet is capable of such ludicrous behaviour. Just us.

Thankfully, humans are willing to share what they have and live in harmony with others, and nature exists.

Whatever…

Back to the semantics. I would understand if you feel hesitant about calling yourself a feminist. No matter how far we have come, many men and women might not feel connected to the term ‘femme’ and perceive it as a ladies-only movement at first glance.

As far as I’m concerned, you can call it whatever you like. Just be self-reflective and recognise the privileges you enjoy and the exclusions others face. Love and respect everyone, stand up against injustice and fight for equality. Believe in a world where everyone’s basic human rights and needs are met, and everyone is respected equally.

This will not only save us from loneliness and moral decay, it could also save the planet.