The AIDS epidemic started 40 years ago. As did the long and laborious battle against HIV. Two colleagues were there in the ’80s in the epicenter of the crisis: the African continent. They take us back to the AIDS frontline. And draw parallels with COVID-19.

In the 1980s, the Netherlands still sent hundreds of healthcare professionals to Africa every year. To work in hospitals and train doctors, nurses, and paramedics. Memisa, a Catholic health NGO and one of the predecessors of Cordaid, was well known for it. Just like ICCO, Cordaid’s protestant counterpart and now merged with Cordaid. Times have changed. Today, mission hospitals and other health facilities in Africa are almost exclusively run by African professionals.

“Gloves and surgical clothes were still washed, syringes were recycled.”

Jos Dusseljee, Cordaid’s senior health expert, works closely with hospitals and governments in countries such as Zimbabwe and Uganda to improve healthcare systems. He is now based in The Hague, but back in the ’80s and ’90s he was a medical advisor in Kenya, Uganda, and other East African countries. In the same period, senior sexual and reproductive health expert Christina de Vries, trained staff and worked as a tropical doctor for ICCO/Kerk in Actie in various hospitals in Africa. Notably in Nigeria.

‘Weird things are happening’

In the early ’80s, Memisa started receiving disconcerting messages from its doctors abroad. ‘Weird things are happening. Death rates are skyrocketing and we don’t know why.’ At one point, the medical director of Memisa, Tom Puls, decides to take a stock of blood samples from Uganda to the Netherlands. Test results are irrefutable. It’s this new disease, AIDS.

“I can still see the bits of colored toilet paper fluttering and blowing away in the strong wind. That’s how they decorated the graves. You were covered in toilet paper.”

It took time for doctors to deal with the new disease. A lot of time. “There was a course at the Tropical Institute in 1985. That was the first time we were taught about HIV and AIDS,” Jos remembers. It was also the year in which Jan van den Hombergh, a Dutch doctor in Tanzania, reported the first two AIDS patients in Memisa’s newsletter.

“It really felt suffocating and risky, in those years, to work abroad as a tropical doctor. HIV tests either didn’t exist or were far too expensive. There was no treatment. We had to wait until 2000 for a combination of drugs that really worked,” Christina recalls. “Gloves and surgical clothes were still washed, syringes were recycled,” Jos adds.

Harsh conditions

Just how risky becomes clear when Henk Engel, a Memisa doctor who had been running a hospital in Kenya for years, gets infected during an operation in 1987. He accidentally cuts his hand. His patient was later found to have HIV. It’s a workplace accident. Treatment in the Netherlands, with the then just registered drug AZT, is not working. In 1992, Henk Engel dies of AIDS.

In countries such as Malawi, Uganda, South Africa, and Nigeria, infection rates among adults reached up to 30%.

Jos, who worked with him at the mission hospital in Kenya: “That fatal incident during the operation did not happen out of the blue. The work pressure of doctors in understaffed and underfunded African hospitals is extreme. Doctors often did ten deliveries a day, in addition to operations, in dire circumstances.”

Christina, who had studied with Henk Engel: “When ill, Henk fought a very important battle against stigma, discrimination, and humiliation of HIV-positive people. He was one of the first who dared to talk openly about his own illness. Who put HIV-related occupational risks in the hospital on the agenda. He insisted on more safety and protection of healthcare workers. He fiercely campaigned for better medical insurance, because tropical doctors at that time could not insure themselves against HIV/AIDS.”

It takes 15 years before well-functioning and affordable AIDS medicines are available on the market, also for patients in Africa. 15 years. And while the medical world is grappling with the new disease, ‘coping in the dark’ as Jos calls it, HIV and AIDS, stigma and exclusion strike mercilessly.

Gaping holes left by AIDS

The world has no answers. In countries such as Malawi, Uganda, South Africa, and Nigeria, infection rates among adults reach up to 30%. The virus is decimating part of the population. Mostly young adults. In the late 1990s, in Malawi, 10% of the households are orphan-headed. In Southern Africa, large-scale Granny Programs supported grandmothers to carry the burden of care of their grandchildren.

“Newspapers were full of obituaries of young people. But not a word about AIDS.”

AIDS-related death rates cause burial congestions. “I can still see myself standing in a cemetery in Lusaka, Zambia. Surrounded by fields full of fresh graves, of people under thirty. Dozens of funeral processions, queueing, waiting. I can still see the bits of colored toilet paper fluttering and blowing away in the strong wind. That’s how they decorated the graves. You were covered in toilet paper.”

In 1996 Christina finances a freezer project in Kenya. “That was for mourning centers, to keep conserve corpses for a longer time and to have burials take place on one day of the week. People had to go to a funeral almost every day. They couldn’t do their job anymore. Newspapers were full of obituaries of young people. But not a word about AIDS.”

In some African countries, life expectancy plummets by 10, sometimes 20 years. Mortality among the working population completely undermines already weak and understaffed systems in health care and education. It shakes entire economies. When Christina returns in 2005 to the hospital in Nigeria where she had worked in the 1990s, she only meets older colleagues. “All the young people I had trained had died of AIDS.”

Sin, disease, and denial

For a long time, the Catholic Church denies what is happening. The link with sexuality is a great embarrassment to religious leaders. In their eyes, ‘true Christians are faithful and cannot get HIV’, or ‘good Muslims cannot get AIDS’. “They were at loggerheads with sin and disease and didn’t want to do the right thing in disease prevention,” Christina says. “The number of funeral masses priests had to perform was a real burden and kept them from doing other things they wanted to do. It was a cause of burnout among many young priests. Still, they continued only preaching abstinence.”

ABC was the mantra at the time: abstinence, be faithful, and, ultimately, condoms. “Often it was ABCD, with the D for ‘or death will follow’. But for the Church, the only real protection, condoms, was out of bounds. That total denial has caused a lot of damage,” says Jos. “It was only much later that the Church began to devote itself to AIDS patients in their final phase of life, to AIDS orphans and other surviving relatives.”

AIDS, a chronic disease

The harrowing AIDS pandemic peaked in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The great shock wave is over. True, after 40 years there is still no vaccine. But combination therapy works well, prolongs life and prevents HIV infections. Drug prices dropped sharply, making them affordable not only for the rich. Treatment of AIDS has become part of regular care, also in Africa. Today, AIDS is a chronic disease you can grow old with.

Patients turned their individual struggle for survival into a collective struggle against stigma and a struggle for fellow sufferers.

So yes, the world did find answers. Also in Africa. Thanks to the thousands and thousands of African doctors and nurses, and tropical doctors from abroad. They kept going, against the grain and sometimes until the bitter end. Thanks also to major investments from the UN and the Global Fund of Bill and Melinda Gates. Thanks to people like Joep Lange, the leading Dutch AIDS expert who died in the flight MH17 disaster. And thanks to millions of AIDS patients themselves, who turned their individual struggle for survival into a collective struggle against stigma and a struggle for fellow sufferers. Like Clarisse Mawaki in Kinshasa.

Yes, answers did come. But it took years. And in those years, AIDS took the lives of 36 million people.

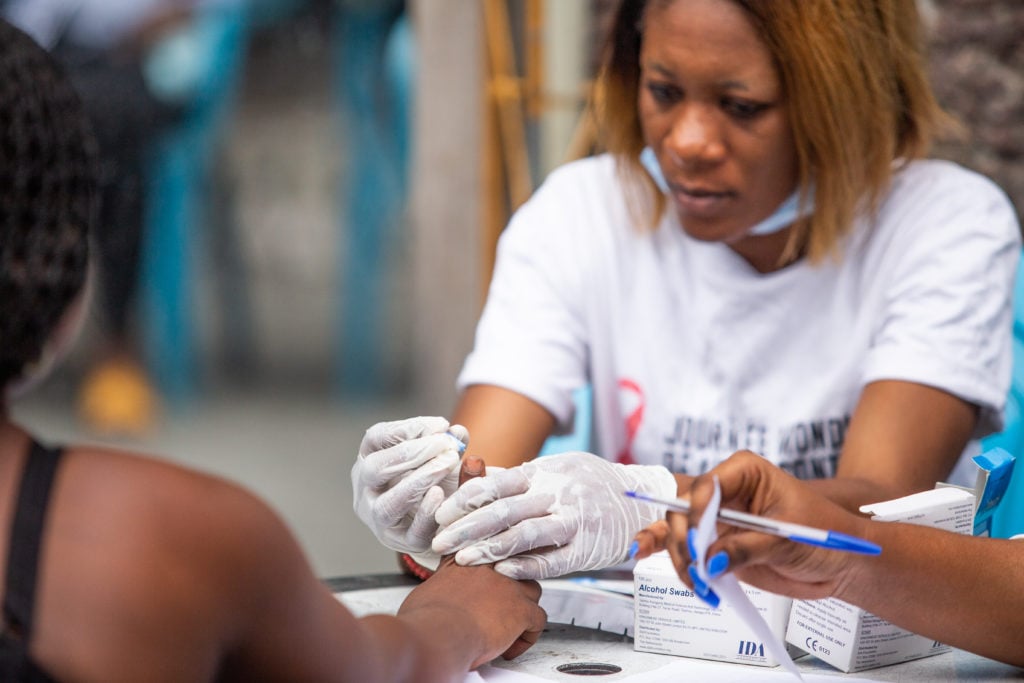

People still die from AIDS, especially in African and Asian countries. 680,000 last year. That is why Cordaid continues to work on preventing the spread of HIV and making AIDS medication accessible to everyone who needs it. In DR Congo, a country as big as Europe, we do this with the generous support of the Global Fund against Aids, TB, and Malaria. The drugs we distribute and the health facilities we support in even the remotest corners are a lifeline to many.

As you can see in this video.

‘We will continue until we have conquered AIDS’

Today, we work differently on HIV and AIDS than we used to. “Our fight against AIDS today, in countries such as DR Congo and Uganda, is part of a much broader campaign for the sexual, reproductive, and other basic rights of young people”, Christina explains. “The battle against unwanted pregnancies and school dropout is also part of this. We promote the right to sexual education. To be able to make your own decisions about your own body, to make your own choices about your own sexuality. We ensure that young people can talk about it, go to centers and facilities where they are really listened to. Where it is normal to talk about contraceptives, especially in countries where there are still so many taboos.”

“‘We want 3 million AIDS patients on treatment before 2003. Five million in 2005, 20 million in 2010’, Joep Lange said. And it worked.”

And of course, we keep supporting hundreds and hundreds of health centers on the African continent, where people can go for affordable professional care. Including AIDS medication. “We’ve been doing that for decades. And we will continue to do that until we have conquered AIDS,” says Jos.

Aids and COVID: parallels and lessons

What do 40 years of fighting AIDS teach us in the fight against that new global virus, COVID-19? Of course, COVID is not an STD. It’s less deadly. The stigma is less. Or different. But can we learn lessons?

“I recognize phases,” says Christina. “First comes the shock, then the denial. This initial reflex of many people, including governments, to say that it is about ‘others’. It doesn’t concern ‘us’. You saw it with HIV, you see it now. You see the same difficulty in educating people who deny the pandemic. They deny that they themselves can contribute or contribute to the spread of the virus. Many countries closed their borders for fear of HIV. The same has happened now.”

“What happened then, and happens again is the extreme overload of health care systems. We’re all seeing it happen, everyone watches, and nobody knows how to deal with it adequately. ‘Work harder’, ‘schedule more’ or ‘this will pass’, is what you hear. Or people start applauding healthcare workers. It’s nice, but of little use. Especially when many of them get infected themselves and have to stop working.”

Be ambitious, work together

“Be ambitious. More ambitious. Maybe that is the most important lesson the long road of the fight against AIDS can teach us today,” Christina continues. “Everyone thought Joep Lange was crazy, with the ambitions he introduced to the medical world. ‘We want 3 million AIDS patients on treatment before 2003. Five million in 2005, 20 million in 2010’, that’s what he wanted. And it worked. So, dare to dream big. Bill and Melinda Gates came with billions for the worldwide fight against AIDS when UNAIDS was still an office with about eight people.”

“And work together across borders, worldwide. Dare to connect. Together we can overcome any virus. Only together,” she concludes.