“We started responding the day Rohingya refugees crossed the border. We will stand by their side until this crisis lasts,” says Shakeb Nabi. He and his team in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, just won a second innovation award for their ‘turning waste into resources’ project. And the community kitchen they support serves thousands of meals a day to survivors of the recent blaze that devastated part of the refugee camps.

Humanitarian work in one of the world’s largest refugee settlement areas means dealing with a thousand challenges at the same time. At the exact moment that we establish an online connection with Shakeb, who is Cordaid/ICCO’s country representative in Bangladesh, COVID-19 messages of a mobile awareness-raising unit flood the streets and totally blur our conversation.

“They are just announcing that we’re going in total lockdown. People are told to stay inside”, Shakeb still manages to explain and then begs to call back later, when the megaphones will have ebbed away.

A city cracking at the seams

In Cox’s Bazar, COVID is just an extra challenge on top of many others. In August 2017, the lush coastal area comprising of two sub-districts with a population of 300.000, saw the start of what grew to become the influx of one million Rohingya refugees fleeing Myanmar. Settling spontaneously, cutting trees, and clearing patches of land on the Chittagong rain forest hills. Building makeshift homes with next to nothing, overlooking the touristy Bengal Bay beaches.

“They were welcomed by the government and by citizens,” Shakeb explains. But nobody foresaw the scale of disruption and tension the refugee crisis would cause in Cox’s Bazar. Existing public services and facilities were completely overstretched. There was a run on resources like fuelwood, on food. Society cracked at the seams. Markets went berserk.

“Prices of food and commodities went up fourfold and labour wages dropped dramatically. This was equally hard for the host community. And don’t forget, Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated parts of the world. Land, to live on and to cultivate, is a rare commodity,” Shakeb continues.

Crisis containment

One way of dealing with the crisis, even literally containing it, was the government’s decision to appoint two sub-districts for refugee settlement, Teknaf, and Ukhiya. Refugees from the Muslim Rohingya minority are not allowed to move beyond these sub-district borders. Recently, an island in the Bay of Bengal was added to the list of settlement areas.

“We work for Rohingya refugees, but even more with them, proud to stand side by side.”

COVID-19 restrictions only compounded the plight of the Rohingya, who are one of the most persecuted minorities in the world. And on March 22nd, when a massive fire devastated parts of Kutupalong-Balukhali camps, Rohingya refugees took yet another blow.

The inferno of March 22

According to Shakeb, the blaze destroyed shelters of 25.000 households. Once again, a cruel twist of fate in the lives of the displaced Rohingya people. It killed more than a dozen refugees. “Just imagine, this was an inferno in a cramped and confined setting,” says Shakeb. “The refugees have settled in an extremely fragile ecosystem. It is prone to floodings, landslides, and other weather-related adversities. And to fire. In no way are they equipped to adequately deal with that.”

Safety, security, and dignity

So, how are we reaching out to those who face this multitude of challenges? “Our job is to increase the safety, security and above all the dignity of the forcibly displaced Rohingya community”, Shakeb firmly maintains.

“Right from the start, in August 2017, we gathered a team of responders who joined hands with the Rohingya community and with the World Food Programme. Today that team consists of a hundred aid workers, here in Cox’s Bazar.”

Myanmar’s current tense political limbo and the state of emergency are only adding to the insecurity of the displaced Rohingya community.

In everything we do, the Rohingya are at the centre. They are not the recipients of aid, they are the driving force of our responses, from start to finish. In Shakeb’s words: “We work for them, but even more with them, proud to stand side by side.”

Keep it local, make it circular

Ecology and circularity are key elements of Cordaid/ICCO’s humanitarian work in Cox’s Bazar. It focuses a lot on upcycling, especially waste material. It promotes the use of local products, boosts local production, and local consumption.

And lastly, we focus a lot on skills training. People we work with can learn new trades, develop new talents and increase income-generating skills. This breaks the hopelessness and immobility of camp life. “And newly learned skills can be useful in the long run when Rohingya refugees will be able to go back home,” says Shakeb.

“Whenever that will be”, he adds rather gloomily. Myanmar’s current tense political limbo and the state of emergency following the military takeover and the ensuing popular protests are not helping. In fact, they are only adding to the insecurity of the displaced Rohingya community.

In the myriad of Cordaid/ICCO relief activities in Cox’s Bazar, two initiatives stand out. One of them is the award-winning turning-waste-into-resources project.

Addressing pollution and joblessness at the same time

This is a project that addresses pollution, ecological degradation, lack of income and employment, and lack of training all at the same time. “The amount of plastic waste in major humanitarian response sites, such as the one in Cox’s Bazar, is massive. It clogs drainage systems, creates severe health risks, and simply adds to the overall bad living conditions of displaced persons,” Shakeb explains.

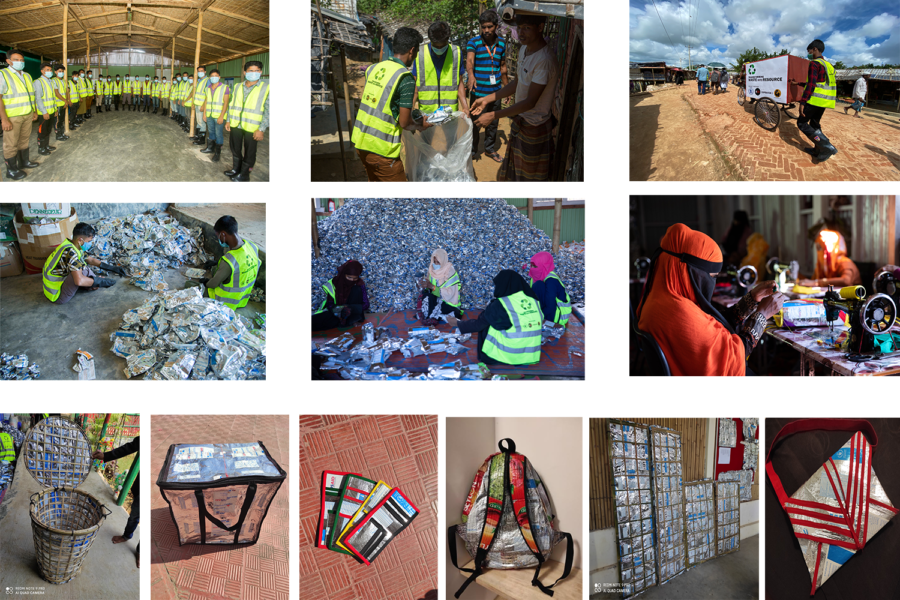

This Cordaid video shows the Turning waste into resources project in Cox’s Bazar.

Hence, 1,5 years ago, Rohingya refugees, Cordaid/ICCO, WFP, and Garbageman, a Bangladeshi social enterprise, joined forces. “Together, we set up a waste management centre in Jamtoli, one of the campsites. Today, about 500 people are involved in upcycling plastic waste into finished and sellable products, such as rucksacks, laptop poaches, bracelets, bin bags, and wallets. They get paid by the World Food Programme for the work they do, whether it’s skilled or unskilled labour. Garbageman brings in the upcycling expertise. And we from Cordaid/ICCO organise skills training, do the centre management, and create awareness about the project. But the driving force is the Rohingya community. They do the work and run the place.”

This gallery shows some of the steps in upcycling waste in Cox’s Bazar:

From collecting and cleaning plastic waste to cutting, stitching, creating, and selling the final products, it is all done in the centre. “The items are sold locally. Actually, the garbage bag is a huge hit,” Shakeb explains.

Most marginalised come first

A lot of the seated work is done by people who have difficulties in walking or standing. For example because of an impairment or disability. “Overall, most of the paid work is first offered to people who have a harder time than others and are often marginalised. Like elderly women with no income.”

The turning-waste-into-resources initiative provides livelihoods and food security to those involved and their families. “It also helps addresses pollution, it’s circular, and it promotes social cohesion,” Shakeb adds.

Given the tense crisis situation in Cox’s Bazar, social cohesion is badly needed. “This initiative shows there’s a value in hosting refugees. They are not just waiting for aid. They create market opportunities and income themselves. And by selling their products locally, they positively interact with host communities,” Shaked says.

Innovation award gives a moral boost (and possibly funding)

Last year the initiative won the World Food Programme Innovation Award. And this year, in March, it won the Bangladesh Innovation Award. “The award is a recognition of our way of working. It gives a moral boost to the teams involved. And it tickles the curiosity of donors. So hopefully, there will be more funding for this work. The prospects are positive already. With WFP support, we are going to start upcycling waste management centres in five other camps, across the settlement areas. Creating green income opportunities for about 2500 other Rohingya refugees and their families.

The importance of serving delicious food

The other humanitarian initiative Cordaid/ICCO and WFP are involved in is more recent and has a similar approach. It too is a food assistance initiative and combines local production with local consumption. “Right after the fire on March 22nd, hand in hand with a group of refugees, we set up a community kitchen in 24 hours. It provides 4000 meals and food packages a day to people who lost their shelters in the fire. Honestly, it’s the best-managed kitchen in the refugee settlement. Rohingya cooks run the place. They serve delicious Rohingya food. I’ll vouch to that for having tasted it myself. Fresh, hot, and made to the flavour and taste of the people.”

Serving not food but delicious food may sound like a minor issue in the epicentre of a major refugee crisis. But good food means more than nutrition. Like good music, it can uplift hearts and souls anywhere in the world. All the more so in Cox’s Bazar.

Looking ahead

When asked to look ahead, Shakeb Nabi isn’t too sure. “There’s COVID and the lockdown, making everything more difficult. Luckily, as humanitarians, we have passes that allow us to move around and do our job. But still, it does complicate things a lot.”

Then there’s the political disarray in Myanmar. “This only casts more uncertainty on the future of the Rohingya refugee community,” says Shakeb “They are one of the most persecuted minorities in the world. They deserve dignity and security, in their homeland. They deserve recognition as citizens, with all the protection that comes with citizenship. We don’t know when that will come. But as long as they are here in Cox’s Bazar and this refugee crisis continues, we will continue to serve them. Both humbly and proudly.”