UN Security Council Resolution 2250 was a landmark for youth’s involvement in peace processes. But seven years down the road, the story of 22-year-old Maimona Abdullah in Yemen shows there’s still a long way to go. “We are the majority. We raise our voices. But most of those in power, the older generation, do not believe in us. They marginalize us. We are held, hostage.”

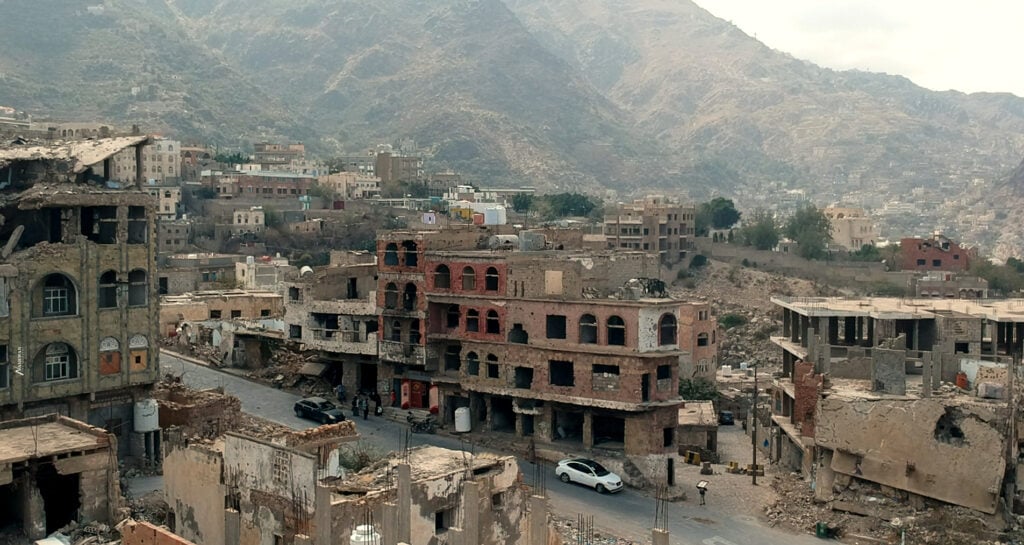

Header image: Maimona Abdullah, graduate in English literature, entrepreneur and peacebuilder who lives in the besieged city of Taiz, in Yemen.

In 2015, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution on Youth, Peace, and Security. It impels decision-makers around the globe to cast a different look on youth. Not as the stereotypical troublemakers or as victims, but as key players in preventing conflict and maintaining peace. UNSCR 2250 wants young people to meaningfully participate in peace processes and urges member states to increase their financial and political support to make this happen.

The landmark resolution was a long time in the making. From 2010 onwards, Cordaid supported some of the lobby and advocacy initiatives that resulted in its establishment. Ever since, together with partners like UNOY and the Cordaid-hosted CSPPS, we have been standing with young people, especially in conflict-affected settings, in claiming a seat at the tables of war, peace, and conflict prevention. After all, when it comes to war and conflict, they are in the thick of it. Their future is at stake. And true peace will never come without them.

Where does it matter most?

No wonder Cordaid was thrilled when UNSCR 2250 was adopted on December 9th, 2015. New resolutions on youth and peace have been adopted since. They all give civil society a more solid ground to advocate for youth’s involvement in peacebuilding, a mirror to hold up to unwilling or evasive decision-makers, and a means to exert more pressure.

“When young people campaign for dialogue and unity across all sectarian divides, things become tricky. Most people in power don’t like that, because it undermines the political game of divide and rule.”

Yes, UNSCR 2250 has been ground-breaking. Especially on paper, and in international circles. But less so inside the realities of conflict and under the domes of fear. True, young people unleash movements of change in their communities, even revolutions. But mostly, ruling powers either don’t listen to them or try to make them shut up. Conclusion: a lot still needs to be done to turn the landmark resolution into reality where it matters most.

Introducing Maimona

Maimona Abdullah in Yemen is one of those young peacebuilders operating under the dome of conflict. Like many peace activists in conflict zones, this former aid worker from Cordaid partner YWBOD takes up a myriad of roles and responsibilities. She is a survivor as well as a visionary, an entrepreneur as well as a poet. She’s a young graduate, a women’s rights activist, and a peace builder.

In the run-up to the 7th anniversary of UNSCR 2250, and as a tribute to Maimona and to all young peacebuilders who keep hope alive in the darkest of times and places, we share her story. We hope it will be shared by others. And that by doing this, in a small way, we can cross cultures and wear down divides.

In this vlog, Maimonah gives an insight into her life. She shows the position of young women in Yemen and offers her views on what must be done to improve this. It is a very personal video that illustrates the local perspectives of Yemen.

‘Roads can be death traps’

“Who am I? A person can get lost in her or his life trying to figure out the answer to this question. Basically, I am trying to be someone who can change the world in a positive way. The easy answer is: I am Maimona Abdullah, 22 years old, graduated recently in English Language and Literature and I live in Taiz, a besieged city in Yemen.”

“My main aim is to change this mindset of fear and ignorance. People need to be aware of their rights. People need to know that inequality and suppression are not God-given.”

“The draconian siege of Taiz has cut off the city and tore it apart, in a Houthi-controlled and a government-controlled area. Roads can be death traps. Access to food, medicines, and goods is blocked. This is a nightmare we have been living in for years. War robs us of our future. Seeing kids younger than myself, who have only known war, is painful. They have no dreams. And youth should be about chasing dreams.”

‘We don’t give up, we don’t give in’

“Yet, despite all this, young people don’t give up. And we don’t give in. A lot of young people have taken to the streets, knocked on doors, and used social media. We are extremely active. Despite the fear, grief, and suffocation of war, we educate ourselves and increase our skills and our talents. We are the majority. We raise our voices, come up with ideas and solutions to end the siege and ask to be actively involved in peacebuilding. Because the horror needs to stop.”

“But the opportunities to participate are slim. Most of those who are in power, the older generation, do not believe in us. They don’t listen. They marginalize us. Yet it is our future they block. We are held hostage.”

“We carry a lot, but we’re not even allowed to contribute to peace. My generation has grown up with politics and conflict. It’s all we hear and see. Everything is political and politicized. It makes us more conscious, but it’s also a burden, especially if you can’t influence decisions.”

‘Normal life? Oh yes, I remember…’

“When young people campaign for dialogue and unity across all sectarian divides, to rebuild Yemen, things become tricky. Most people in power don’t like that, because it undermines the political game of divide and rule. The result? A lot of young activists and journalists have been kidnapped or jailed. We don’t know their whereabouts.”

“Young people are not waging this war, but we are all victims. It’s not necessary to be killed to be a victim. We may be alive, but our rights, our future, and our normal life have all been killed. Normal life…What is that? Oh yes, I remember. It means walking around without the fear of getting a gun against your head. Without the fear or the grief of losing someone.”

“All this cannot stop young people in Yemen. We are like water, we seek our way through. I worked with the Youth Without Border Organisation for Development, a Yemeni NGO. But I also wanted to be successful in business. At the moment I am working for a big corporation in Yemen.”

“With Cordaid’s support, I was part of the team that produced the video Amal, which means hope. It shows the destructive mental impact of war on young people.”

“I’m also a writer. I recently won an award for one of my short stories in Arabic, called A shadow in Al-Ashrafiyyah. It’s about a girl going on an imaginary journey. But it’s also about the impact of war on Taiz city and on its citizens. And about how, when people become too religious, they lose their sense of logic and become extremist.”

‘Inequality is not God-given’

“When the revolution came in 2011, this was a burst of awareness. It created cracks in a sexist, oppressive collective mindset. The war, fuelled by fear and ignorance, quenched this. My main aim is to change this mindset of fear and ignorance. People need to be aware of their rights. They should be able to hold their leaders accountable. People need to know that inequality and suppression are not God-given.”

“Here I am, a strong young woman in Yemen, one of the worst places in the world to be a woman.”

“Claiming superiority over others – one group over others, men over women – cannot be normalized just because you call it a tradition. The only way this country can come to terms with itself is when every one of its citizens can take part in rebuilding it. And that can only happen if people open their eyes and their minds.”

‘Luckily the revolution planted seeds’

“Being young in Yemen is hard, being a young woman is a lot harder. Young men aren’t listened to, young women aren’t even seen. We are invisible. There is a handful of Yemeni women who managed to become influencers and take part in peacebuilding processes. But at what cost? They are constantly bashed both by society, by people in power, even by their own family.”

“Physically, mentally even genetically, women are considered inferior. Fighting this destructive prejudice is a constant uphill battle. Some men constantly tell me I can’t be anything – at work, in college, in the street. This destroys the energy inside of you. But I fight back by being better than them. Luckily, the revolution planted seeds. Also in the minds of young men. Some think and act differently, also towards women. Myself, I was lucky to have a supportive dad. He believed in me and valued me as much as my brothers. For him, personality came before gender. And here I am, a strong young woman in Yemen, one of the worst places in the world to be a woman.”

‘In the end, I will know who I am’

“We started by asking ‘Who am I?’ I am all of this, an activist, an entrepreneur, a poet, a writer, a graduate, a young woman who helps kids in her street with their homework, a daughter, a girl in a warzone… I am a peaceful warrior whose aim is to keep all these parts together. The mosaic will grow and in the end, I will finally know who I am. And what I have been able to achieve.”